- Navigator

- Expansion Solutions

- Industry Analytics and Strategy

- Real Estate Development and Housing

- National

This article originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of Expansion Solutions.

What Is a Science and Technology Park?

Science and technology parks have various definitions and, therefore, mission, goals, and objectives. These have changed over time as technology, economy, and culture have changed and vary depending on the perspective of the park’s designers, developers, and stakeholders.

The Association of University Research Parks (AURP) is a leading network and services organization for member parks and related stakeholders. They provide information, best practices, training, and resources on science and technology parks, but refer to them more generally as “research parks” and “innovation districts” and define them as: “… physical environments that can generate, attract and retain science and technology companies and talent in alignment with sponsoring research institutions that include, universities, as well as public, private, and federal research laboratories. Research parks enable the flow of ideas between innovation generators, such as universities, federal labs, and non-profit [research and development] institutions and companies located in both the research park and the surrounding region.[1]”

Their definition is understandably centered around university research but expands beyond the “park” concept to include “districts.”

Building on past definitions and considering that my focus is typically on economic, workforce, and community development, I offer a simplified definition as follows: The convergence of knowledge (science), technology, industry, and place attempting to create an innovation and economic ecosystem that includes the strong presence of and connection to a research entity or entities.

In this article I will use this definition to help describe common characteristics of science and technology parks, recent and emerging trends, and recommendations for economic and business developers. This is meant to be relevant to anyone seeking to develop or grow science, technology, and innovation-based economic development regardless of whether it is within a specific park or within a larger district.

Common characteristics of science and technology parks or districts include:

- Direct and supporting entities, activities, and infrastructure including facilities, equipment, and supporting infrastructure (power, telecommunications, roads, etc.) for research and development (R&D), innovation, technology, commercialization, and business growth

- Entrepreneur and business start-up, technology transfer, incubation, and acceleration services/facilities

- Typically, there is an entity overseeing the management and operations of the park or district for the benefit of the tenants and stakeholders and works to fulfill the park’s mission

- May have a master plan that conforms to anchor or sponsor university and institute plans, as well as the local governing authority. This plan is meant to guide design, development, infrastructure, amenities, public spaces, etc. to provide consistency and establish a long-term vision for the park

- May have or attempt to have anchor/connected private businesses or areas within park for business growth beyond the startup and acceleration phase

Brief History and Recent Trends

Science and technology parks have been around since the early 1950s and they exist across the globe. “Stanford Industrial Park, established on land owned by Stanford University near San Francisco in 1951, is considered the first such park, and played a key role in the development of Silicon Valley. Today, according to the International Association of Science Parks and Areas of Innovation, parks are in operation or under development in virtually all developed countries and at least 36 developing countries.[2]”

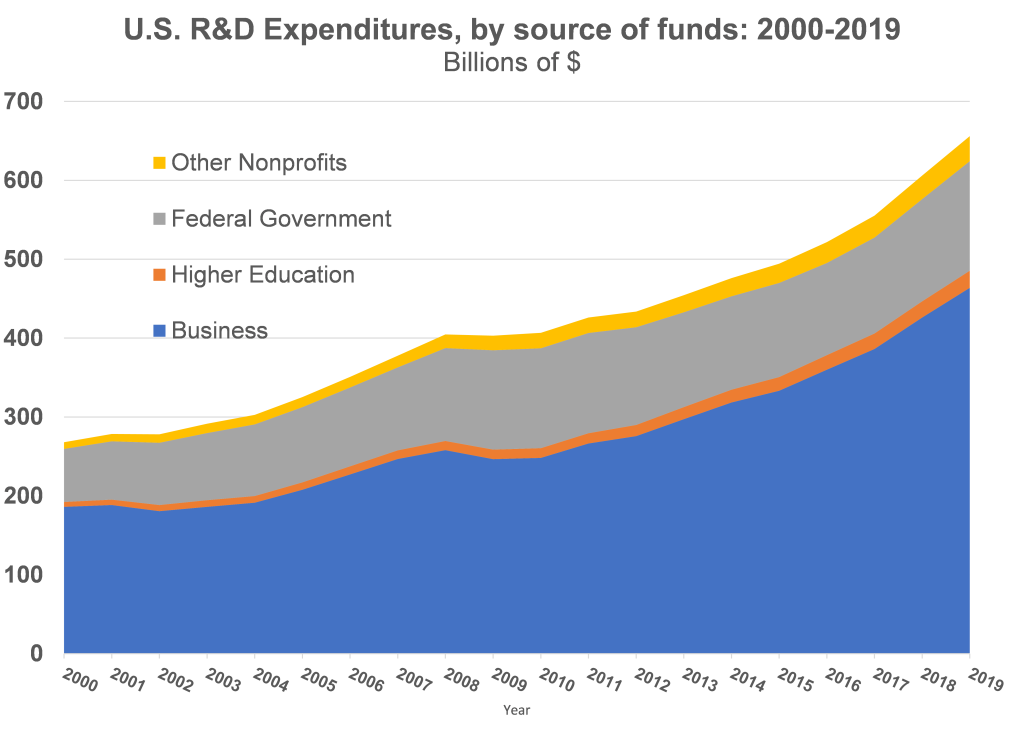

In the U.S., the parks grew as R&D funding grew, and they continue to be highly influenced by R&D funding, which in the past two decades has been increasing and driven by private sector sources. In 2019, R&D expenditures in the U.S. totaled $656.2 billion from the major sources (business, higher education, federal government, other nonprofits). This is up from $268 billion in 2000 (see Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1

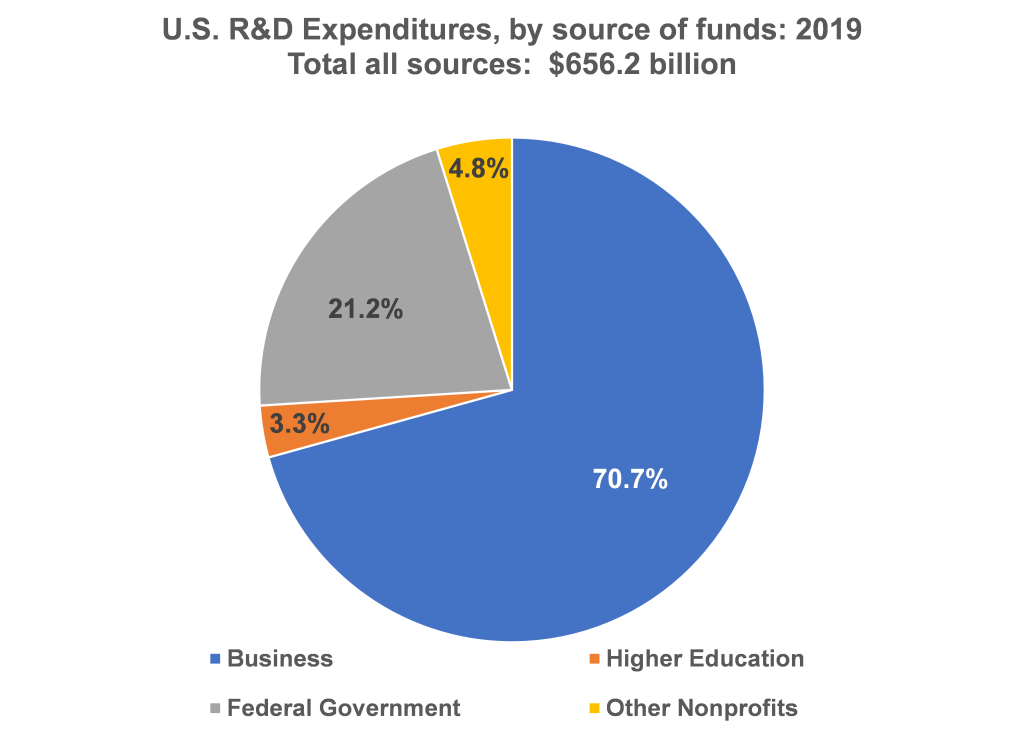

Funding by business for R&D has steadily increased as a percentage of all sources and, in 2019, totaled $463.7 billion, representing 70.7% of R&D expenditures from the major sources (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Based on the data, it is no surprise that science and technology parks and districts have become increasingly driven by, or inclusive of, private sector, R&D-intensive businesses and industry. Several other factors and trends are also impacting science and technology parks and districts.

Chief among the changes impacting science and technology parks and districts is the digitalization of culture and the economy. We are in the age of the tech (IT) of everything. This impacts both the technologies in the parks and districts that drive R&D, commercialization, and industry, as well as the premise upon which the parks are based: innovation and related economic benefits occur more rapidly and robustly in places where people can physically connect and collaborate.

In terms of the technologies driving the R&D, commercialization, and industry, the R&D-intensive fields like biology and life sciences, advance materials, energy, and advanced manufacturing all are driven by advances in digital technologies, including computing speed, computing storage, and telecommunications. Therefore, the parks and districts now all relate to information technology sectors and top skills and occupations such as software analysts, quality assurance specialist, data scientists, and network specialists. Regions and localities without such capacities, including talent, will be challenged to fully benefit from science and technology park and district activity.

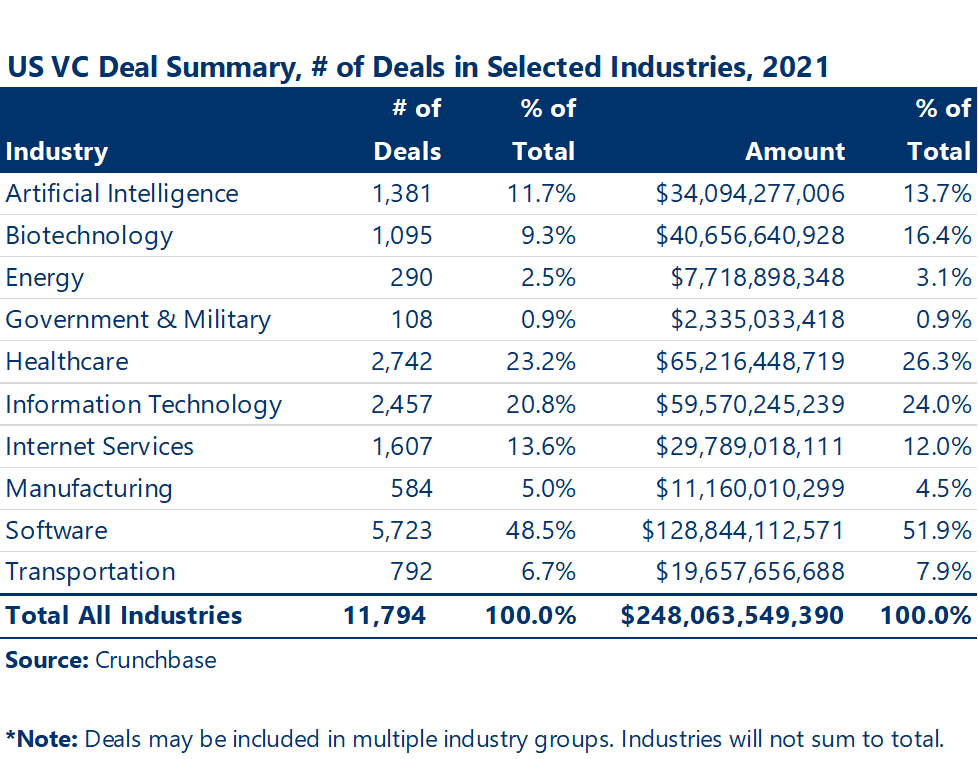

Recent data on venture capital investments supports the finding of the increasing impact of IT and digital technologies on commercialization and growth. In data gathered from CrunchBase, Camoin Associates recently tabulated and assessed venture capital deals and dollars by technology sectors and/technology areas. The 2021 data reveals significant levels of venture capital in information technology and related technologies, including artificial intelligence, internet services, and software (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Digitalization is making the key premise that physical proximity matters to collaboration and innovation less true but has not eliminated it. As IT infrastructure, hardware, software, and “flesh ware” (people) capacities in IT have advanced and been adopted into all aspects of our lives, there is a greater ability to collaborate and innovate remotely and virtually. Yes, people are social and still need to be in-person at least some of the time for relationship building, but remote/digital engagement and collaboration has been greatly improved in recent years, including our own ability to use the technology available.

Think about your own work environments. Remote work skills and practices existed prior to COVID but the supporting technology and individual skills and culture were limited. In repose to COVID and driven by necessity, digital and virtual adoption accelerated. More and more people have become more skilled and comfortable adapting to remote work and digital collaborations. In fact, many in the fields of R&D, technology, science, and related fields and industries have grown up as digital natives where technology has always been ubiquitous. The potential negative impacts of not being “in person” are now being weighed against the benefits of being able to collaborate “anywhere, anytime.”

Technologies and their adoption—including virtual reality, augmented reality, digital twins, 5G, and satellite alongside the spread of fiber improving access and communication speeds—are driving the digital trends and changes to the way we learn, work, and collaborate. And while this will not mean the end of science and technology parks and districts, it will continue to change how they are designed, built, and operated with many variations of hybrid physical and digital collaboration occurring simultaneously.

Other changes and trends are also impacting science and technology parks and districts. Science and technology parks traditionally have been fairly one dimensional in scope, designed and operated to be highly focused on the facilities, buildings, and equipment needed to support science and R&D, as opposed to integrating the needs and energy of the larger surrounding community and ecosystem. Recently this has been changing, as more science and technology parks and districts transform into integrated mixed-use developments featuring housing, retail, commercial office, co-working, accommodations, food, recreation, and public and open spaces all in one place. This is being done to better integrate the goals and objections of science, technology, and innovation-based economic development with local and regional economic, community, and workforce goals.

Just like across all other types of development, the design and construction of science and technology parks and districts are also responding to community and cultural demand to become “green” through:

- Using renewable energy sources, such as on-site solar and bioenergy

- Energy purchases

- Building energy efficiency into facilities and operations from energy to water and sewer to heating and air-conditioning

- Increasing recycling and material use reduction

- Building to LEED[3] certification standards

This is occurring as awareness grows about the environmental impacts within the industry and notions that high-tech energy uses are “clean” are challenged or dispelled. These greening trends will continue to grow and impact science and technology parks and districts, as well as their tenants.

Finally, increased public scrutiny and focus regarding economic and community impacts, return on investment for communities and regions, and equity is impacting science and technology parks and districts. This is driven by a combination of factors, including cultural demand for greater transparency in education, industry, and government; greater scrutiny of development projects; and competing demands for public resources for alternate needs and opportunities

In short, as in with most areas of our economy, rapid changes in technology and culture have necessitated transformation, and science and technology parks and districts are no exception.

Measuring and Understanding Economic and Community Impacts

Once generally viewed from a development perspective as a great investment in the future, science and technology parks and districts are no longer a “slam dunk” for public and stakeholder support. Park development and operations leadership must now objectively consider and reflect the needs, concerns, goals, and objectives of the surrounding community and region prior to development and throughout the life of the site. In other words, there is a demand to take a more holistic approach to the development and operation of science and technology parks, including measurement of the benefits, costs, and impacts to communities, regions, and society.

A global assessment of science and technology parks highlights the need to challenge assumptions and more closely scrutinize park and district development and operations. “Placing the physical infrastructure of a science and technology park is often straightforward. To make it work, however, is more complicated. Only 25 percent of science and technology parks in an advanced economy could be regarded successful in achieving their goals.[4]”

A good example of a science and technology park taking a holistic approach is the University City Science Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the center’s 2021 Impact Report they clearly state as a primary goal and then proceed to measure the following: “Serve Our Local Community – We will address diversity, healthcare, and economic disparities in Philadelphia by nurturing talent in our local community.[5]”

SIDEBAR

Key Metrics for Science and Technology Parks and Districts

The following is a list of metrics for considering performance and economic and community impact of science and technology parks and districts. They are taken from a review of impact studies and annual reports of parks and districts as well as consideration by the author as to what is further needed going forward:

Overall

- Dollar value of R&D performed

- Start-ups created and served plus survival rate

- Graduation location of startups – in park, in region, out of park

- Employment growth by companies served by or within park

- Capital raised – venture capital etc.……

- New businesses attracted to region

- Growth in established businesses

- Create high-paying jobs

- Wages generated

- Sales and taxes generated

University

- Publications produced

- Patents

- Licenses for technology use

- Spinouts – companies started from R&D activities

- Sponsored research- Extramural funding

- Improved placement of doctoral graduates

- Enhanced ability to hire preeminent scholars

Real Estate Related

- Squared feet leased

- Vacancies and vacancy rates

- Lease rates

- Real estate taxes generated

2.0 Metrics – metrics to address cultural and economic changes

- Workforce and education – Connection to education including K-12, community college and beyond, STEM initiatives

- Fit with local and regional economy including vision and goals, workforce and industry strengths and opportunities

- Mixed development use performance

- Local and regional contractors and relationships with companies and entrepreneurs within the region

- Equity – Demographics of workers within park and district, companies with a minority founder/owner

- Green – LEED certification, energy sources

- Ecosystem presence, strength – social network analysis

Case Studies and Best Practices

The following three cases are different in terms of geography, industries, economy, contact, and approach, and are each good examples of responding to current and emerging economic trends.

University of Arizona (UA) Tech Park[6]

Under the umbrella of Tech Parks Arizona, it is a comprehensive, university-led science and technology park that encompasses:

- UA Tech Park at Rita Road – the original science and technology park with 1,282 acres and 2 million square feet of facility space for R&D and offices, and 6,000 workers. Includes the Solar Zone, a multi-technology solar demonstration site that integrates power generation and distribution, R&D, assembly and manufacturing, and new product development

- UA Tech Park at The Bridges – the newest area under development, it integrates technology companies within a mixed use-area that includes residential, retail, and recreational areas. Heavy focus on applied research, innovation, and commercialization. Planned for 65 acres and designated as a tech park and 350-acre multi-use development

- UA Center for Innovation – offers programs and facilities for business incubation and start-ups and connections to university research

In terms of economic development, UA Tech Park provides a good case study of best practices for several reasons. First, it is highly connected to core practices of economic development, including business attraction of targeted industries that align with the region and state (including advanced energy, arid lands agriculture and water, health and biosciences, and more); and provides facilities, programing, and resources to support entrepreneurs and start-ups.

Second, it is transforming over time to respond to cultural changes and related community development through integration of mixed use-development, including residential, office, recreation, and open space—all creating a place-based ecosystem.

Third, it tracks and reports economic impacts with an estimated statewide impact of $2 billion and $52.8 million in tax revenues for the state, county, and city governments[7].

Finally, it was founded on and remains guided by stated founding principles that encompass management and operations, as well as economic, community, and workforce development, and environmental sustainability[8].

UA Tech Park Key Takeaways for Economic Development

- Integrate multi-use/mixed use

- Ensure community and regional fit and relevance, including strong connection to business attraction efforts and regional industry strengths and targeted industries

- Measure impacts

- Build and support innovation ecosystem

- Clearly state and be driven by a mission and values

- Be sustainable/green

Tallahassee Innovation Park

Innovation Park is a collaboration between Leon County Research and Development Authority, the City of Tallahassee and Leon County, Florida, through the Office of Economic Vitality, Florida State University, Florida A&M University, and Tallahassee Community College. The park has a simple and clearly stated mission connecting it to economic development: “… to foster the startup, growth, and attraction of private companies that create high wage jobs and contribute to our region’s innovation ecosystem.” [9]

Innovation Park includes:

- More than 1 million square feet of space in 17 buildings

- Over 30 organizations ranging from university research facilities to specialty manufacturing companies and state and federal government research spaces

- Research centers with global reach and reputation including:

- National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (MagLab)

- High-Performance Materials Institute (HPMI)

- Center for Advanced Power Systems (CAPS)

- FSU Applied Superconductivity Center (ASC)

- Florida Center for Advanced Aero-Propulsion (FCAAP)

- FAMU Center for Plasma Science and Technology (CePAST)

- Center for Intelligent Systems, Controls, and Robotics (CISCOR)

Innovation Park is a local and regional economic success and example of best practices for science and technology parks for several reasons. First, there is a strong alignment between the R&D strengths within the park, higher education degrees, and the target industries within the Office of Economic Vitality’s attraction strategies:

- Applied Sciences and innovation

- Manufacturing and Transportation/Logistics

- Professional Services and Information Technology

- Health Care

This includes connection to the full value chain from R&D, to start-ups, to mature companies involved in manufacturing. This is an important, but often overlooked or misunderstood component in leveraging science and technology parks and districts for economic development. On their own, science and technology R&D creates economic benefits, including direct jobs, sales, and purchases.

However, if connections can be made and leveraged to support companies further producing products and components related to the R&D, the impact can be even greater by retaining the economic benefit in the region. This includes adding and supporting jobs in manufacturing and logistics not typically found within science and technology parks.

A great example of this at Innovation Park is the growth and success of Danfoss Turbocor. A market leader in development and production of compressors, they moved to Innovation Park in 2005 from Montreal, Canada. In 2021, Danfoss broke ground on a new advanced manufacturing facility that expanded their footprint and impact at Innovation Park.

“The project is a multi-million-dollar investment in a new 65,000-90,000-square-foot facility to be built on 16 acres of land. The project will create approximately 239 high wage jobs in manufacturing and R&D over the next several years. This new facility will expand Danfoss’ current 125,000 square feet presence at Innovation Park, which includes engineering and manufacturing operations, an Application Development Center opened in 2017, and training, customer experience, and office space added in 2019.”[10]

Second, is a commitment to supporting an entrepreneurial ecosystem. North Florida Innovation Labs (NFIL) is in Innovation Park and offers incubation space, programs, and services, including connection to the R&D and related assets in the park. NFIL was established in recognition that science and technology parks need commercialization and entrepreneurial capacity and commitment to reach their full potential. NFIL is about to be expanded significantly into a new 40,000-square-foot facility thanks to collaborative funding from Florida State University, Tallahassee-Leon County Office of Economic Vitality, and the Federal Economic Development Administration.

Third, is the commitment to improving the park as a “place” and connecting to Tallahassee and the surrounding region. Plans are underway and construction is scheduled to begin in 2023 on Airport Gateway “to create a beautiful, safety-enhanced, and multimodal gateway between the Tallahassee International Airport and Downtown Tallahassee.”[11] This project both creates better access to Innovation Park but also connects all the surrounding critical assets, including university campuses, downtown Tallahassee, and Tallahassee International Airport. It enhances the brand of the park and the area as a signature place for living, learning, and working.

Innovation Park Key Takeaways for Economic Development

- Collaborate – in this case, with two universities, a community college, a city and county, the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (MagLab) Lab, and more

- Fit with research and local economic strengths and act through business attraction, entrepreneurship, and workforce strategies

- Respond to the changes in the development market for improved transportation corridors and connections

City of Markham, Canada

The City of Markham is located within the Greater Toronto Area of Southern Ontario, Canada. It is home to an example of an “innovation hub” that, while technically not a science and technology park, provides a good example of best practices for growing science and technology-intensive economic development connected to place. The city’s collaborative approach created a hub among key partners and assets that include:

- IBM Innovation Space at the Markham Convergence Centre[12]: 50,000-square-foot space anchored by IBM, which has its Canadian headquarters in Markham

- ventureLAB[13]: Serves as a connector for entrepreneurs and start-ups to the IBM ecosystem, including IBM technologies, and provides services, programs, and facilities

- Innovation York at York University[14]: Part of the York University system and connecting the university to the innovation ecosystem and the Markham Convergence Centre

- Senaca College, Senaca Innovation[15] and Helix[16]: Applied research, though not on the Markham campus, is an integral part of the hub. The incubator provides students, graduates, faculty, staff, and members of the community with facilities and services, including coaching/mentorship, co-working space, networking, funding application assistance, and learning opportunities. Seneca College has campuses throughout the greater Toronto region, including Markham. Applied research centers include Data Analytics Research Centre (DARC) and the Open Source Technology for Emerging Platforms (OSTEP)

The hub approach works for Markham because it fits with the city and greater region’s strength in corporate information technology. Markham has more than 1,500 technology companies employing more than 37,000 people. The Canadian headquarters includes “IBM, AMD, Redline Communications, Real Matters, OnX Enterprise Solutions, Huawei Technologies, Lenovo, GE Energy, Nexeya, Toshiba, Adastra, CDI, Qualcomm, and Genesys.”[17]

City of Markham Key Takeaways for Economic Development

- A tech-intensive company anchored by IBM’s Canadian headquarters

- Fit within a region, like greater Toronto, that is a global leader in information technology

- Foster partnerships with higher education

- Provide entrepreneurial facilities, programs, and ecosystem focused on information technology assets and strengths

Lessons for Science, Technology, and Innovation-led Economic Development

Science and technology parks have existed for many years across the globe. They have had mixed results in achieving economic outcomes and relevance to local and regional economic development. Rapid changes in technology, culture, and economy are making it necessary to transform how we plan, organize, and operate all aspects of our society and economy—science and technology parks and districts are no exception. The above cases and related research point to several lessons for leveraging science and technology parks and districts to enhance economic and community impacts. They are:

- Connect to the value chain beyond the science and technology R&D: This includes industries, products, and services, and the related workforce, across the supply and value chain that benefit from and use the R&D. Start by creating “industry verticals” that relate to and support the R&D and then integrate into the business attraction and retention workforce, and entrepreneurship strategies.

- Design, build, and operate the park and district to meet the holistic needs of the surrounding community and region: This includes multi-use development, transportation, and environmental sustainability. It requires alignment with local and regional land use and related plans and strategies and diversifying the stakeholders engaged in planning and operating the park or district.

- Measure potential impacts and include measures that extend to the holistic approach and emerging trends: This includes sustainability, community and workforce development, and equity. Impact analysis must be built into operations and management and not left to occasional studies.

[1] www.aurp.net/what-is-a-research-park

[2] Policies to promote collaboration in science, technology and innovation for development: The role of science, technology and innovation parks, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Trade and Development Board, Investment, Enterprise and Development Commission, Seventh session

Geneva, 20–24 April 2015, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ciid30_en.pdf

[4] Establishing a Science & Technology Park is No Walk in the Park, by Tengfei Wang (Bangkok), August 16, 2019. Inter Press Service. https://www.globalissues.org/news/2019/08/16/25566 and quoting stats from https://unctad.org/meetings/en/SessionalDocuments/ciid30_en.pdf

[5] https://sciencecenter.org/our-impact

[6] https://techparks.arizona.edu/tech-park

[7] https://techparks.arizona.edu/parks/ua-tech-park/economic-impact

[8] https://techparks.arizona.edu/about-us/guiding-principles

[9] https://innovation-park.com/

[10] https://innovation-park.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Project-Juggernaut-Press-Release-final-edit.pdf

[11] https://blueprintia.org/projects/airport-gateway/

[12] www.markham.ca/wps/portal/home/business/economic-development/hi-tech-and-innovation/innovation-talent/02-innovation-talent

[13] www.venturelab.ca/about

[14] https://markham.yorku.ca/ibm-innovation-space-markham-convergence-centre/

[15] www.senecacollege.ca/innovation/research/centres.html

[16] www.senecacollege.ca/innovation/helix/helix-process.html

[17] www.markham.ca/wps/portal/home/business/economic-development/hi-tech-and-innovation/high-tech-capital/01-high-tech-capital