- Navigator

- State

- Organizational Planning

- Strategic Planning

No two states do economic development the same way. That’s the epitome of the American experiment, where the US Constitution provides each state a lot of leeway in regulating intrastate commerce.

No two states do economic development the same way. That’s the epitome of the American experiment, where the US Constitution provides each state a lot of leeway in regulating intrastate commerce.

Today, economic activities that occur solely within the boundaries of a particular state are generally the domain of economic development. With several thousand counties and 35,748 sub-municipalities across the nation, there are, quite literally, millions of variables at play that separate the leaders from laggards.

The question becomes how does any state (including the District of Columbia and US Territories) capitalize on all its many assets at the local level to stand out and best compete in the world? Incentives offered by many to encourage economic activity are the most obvious examples of how places can stand apart. But they do not determine success, not by a long shot.

The more fundamental factors are the leadership provided by governors and legislatures, and how local municipalities work with their state leaders and each other to advance economic development goals and objectives. How those factors are leveraged makes all the difference between places that prosper and those that do not.

First, is leadership. The one constant in states that are hot innovative engines for economic progress is whether the highest elected leader “gets” economic development.

Is that person

- leading the charge with enthusiasm and extraordinary energy, or are their interests focused elsewhere?

- demonstrating an innate passion and deep understanding for making economic changes happen, or just showing up, reading the script, and appearing to manage through press releases?

- hiring professionals and placing economic development as their top goal, or at least, in their top three goals, or do their interests in creating jobs drop off once they are in office?

- becoming personally engaged in developing strategies, meeting with companies, allocating resources, and aligning departmental efforts, or are they difficult to engage?

- partnering without partisanship with legislative leaders to execute a shared economic agenda, or do they obstinately stand apart from the process?

Ironically, most states lack such leadership. At any given time, my experience shows that only a handful of states have it. When it happens in your state, you know it. Economic development takes center stage, and it becomes fun. It’s painful to do economic development if you have less than committed people, or worse, knuckleheads, at the helm.

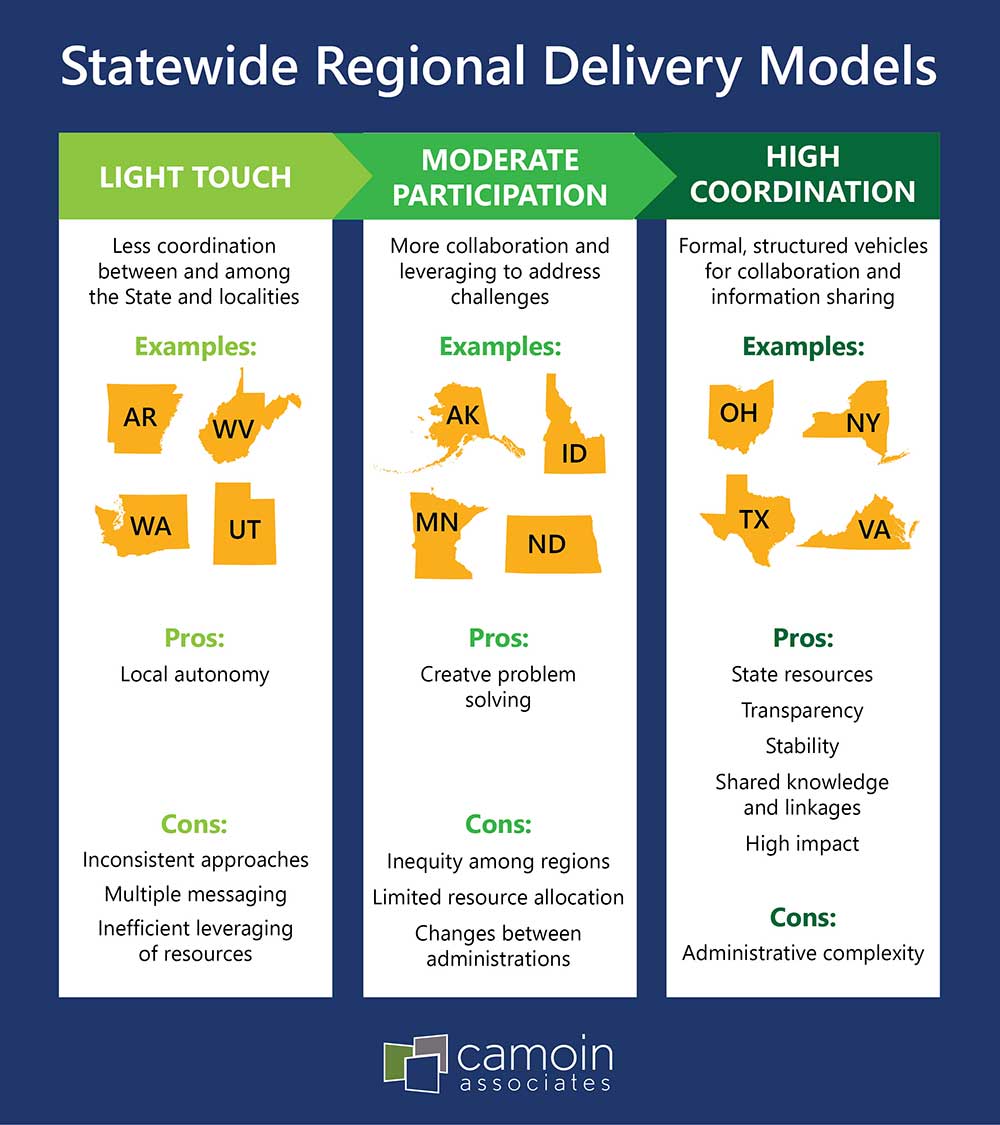

The second influence of success shows up in the way economic development is done. There are generally three ways state government can coordinate activities at a local level to advance the best economic interests of the entire state: Some have a light touch, others demonstrate moderate involvement, while a small number provide a high level of coordination.

One approach is not necessarily better than another. Most states fall somewhere in the middle but no matter which of the three approaches your state follows (light, moderate, or high), great things are only possible if there is committed and competent leadership at the top that is pushing for results.

At the light-touch end of the spectrum, some state governments exhibit minimal coordination between state agencies and localities (e.g., New Hampshire) and some (e.g., West Virginia) concentrate activities in the state capital and deploy regional economic development representatives. Others turn to regional groups (e.g., Arkansas, Utah, Washington) to advance economic goals, deferring heavily to localities to set priorities.

States that demonstrate moderate engagement with the local economic process usually organize activities at regional levels, often leveraging regional planning and transportation efforts for more enhanced programming. In Alaska, nine regional development groups are designated throughout the state to serve as economic development champions, and Vermont takes a similar approach with 12 regional development corporations. Idaho’s Economic Development Districts act as regional organizations aiding local governments in securing private resources and fostering regional cooperation.

At the other end of the spectrum lies high coordination, where states use structured and formal collaboration models. Ohio earmarks funds from its taxes on liquor for economic development, channeling these resources through regional groups for various initiatives.

New York’s approach involves 10 regional councils fostering public-private partnerships to streamline statewide grant processes, resulting in substantial contributions to job creation and community development projects.

Texas showcases diverse economic development organizations where municipalities redirect local sales and use tax, empowering economic development organizations (EDOs) to fund projects spanning from industrial development to cultural enhancements.

Virginia’s GO Virginia program illustrates an intricate collaboration model across nine economically aligned regions, leveraging legislative funding for projects encompassing infrastructure, workforce development, and small business support.

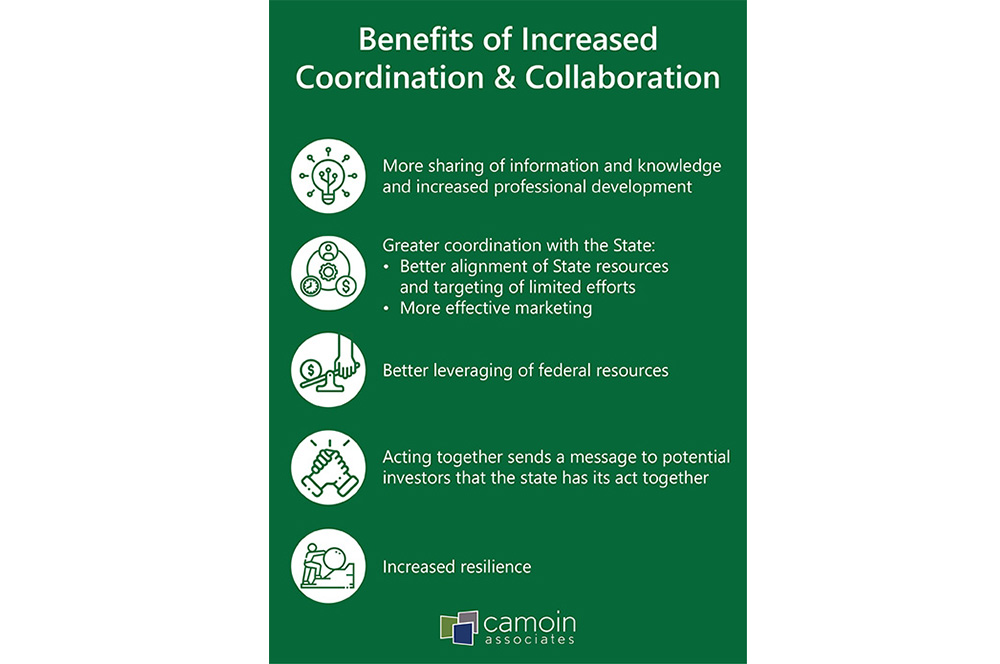

Regardless of approach, the governor and legislature must, however, maximize the potential for greater coordination and collaboration amongst stakeholders to have any prayer for advancing. That is the key. They need to help foster ever-increasing information sharing and coordinate state resources to target efforts that bolster economic activity.

However, each engagement level has its downsides. Light-touch approaches may suffer from inconsistent strategies amongst municipalities and regions, while high coordination includes administrative complexity. All are subject to potential instability during political transitions.

Despite these challenges, all three types of approaches must adapt to the realities of regional economic development as the most logical and effective way to support dozens if not hundreds of sub-municipalities. States need to navigate these nuances, aligning administrative structures and funding mechanisms to amplify regional potential.

In the intricate web of economic progress, states can serve as architects, crafting mechanisms that harmonize local autonomy with cohesive regional development. By placing improved coordination and collaboration as the hallmarks of progress, they propel regional economies toward innovation, resilience, and sustainable growth.

Learn more about our Strategic and Organizational Planning Services